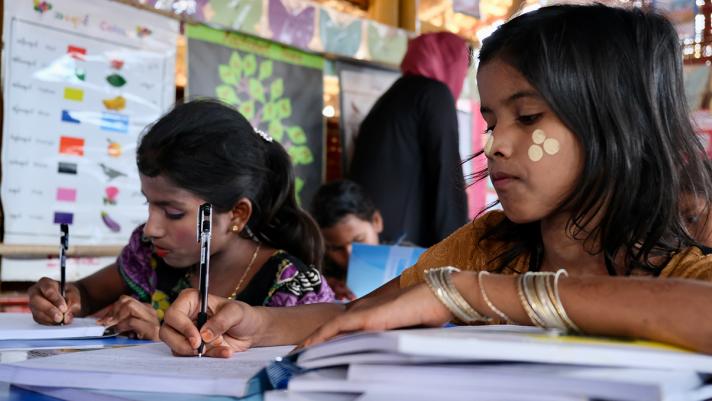

It’s the first day of school for Haresa and Shokatara!

The two girls live in Cox’s Bazar, the largest refugee camp in the world hosting close to 1 million Rohingya refugees. Here, where over 50% of refugees are under 18 years old, the EU is supporting access to education through UNICEF.

For refugee children, learning centres do not only provide education. They also offer social interaction and psychosocial support.

Without the safety net that learning centres provide, Rohingya refugee children especially girls are more vulnerable to abuse, child marriage and child labour.

It’s the first week of a new formal education programme in the Rohingya refugee camps. Children have gathered in a UNICEF learning centre for a lesson Burmese.

2 girls, Haresa and Shokatara, sit together behind a cyan blue desk and giggle. It’s the first time both of them have ever been in a proper classroom.

Red lipstick, black eyeliner, and a golden necklace – Haresa, who is only 12 years old, has put a lot of effort into her appearance. For her, it is a big day and a dream come true.

Even though Burmese is the official language of Myanmar, Rohingya is the native language of the refugees and which they speak at home.

Haresa and her parents understand the benefit of learning Burmese.

When the family first came to Bangladesh, they enrolled Haresa into a learning centre, offering non-formal education on a tailor-made curriculum.

But she dropped out very soon because the family didn’t feel comfortable that the girl’s teacher was a man.

For a while, she had a private tutor who taught her basic literacy and numeracy.

Now she can study in girls-only classes with female teachers that UNICEF introduced as part of the Myanmar Curriculum Pilot. After completing a placement test, she was enrolled into grade 6.

Haresa is excited to start her studies, she was even more excited when she saw her best friend Shokatara in the same classroom.

“I’m so happy because my best friend is here. She is always by my side, always shares everything with me. Now we can study together too,” she says.

“Education is so important. Educated people can contribute to family and society”, Haresa explains, with a big smile on her face.

Shokatara’s cheeks are adorned with yellow thanaka paste, that is traditionally used by Rohingya women as sun protection and make-up.

The girl uses face decoration because it makes her happy. Being 11 years old, she has just entered adolescence.

Adolescence is a critical period for individual identity development, an age for exploration and creativity.

But for Rohingya adolescent girls, like Haresa and Shokatara, opportunities for self-expression are limited.

Education gives girls a rare chance and a safe space to contemplate who they are in the world. That is why both girls are so keen to learn Burmese. It connects them to their homeland and contributes to the sense of belonging.

In addition to Burmese, Rohingya children learn English, math, geography and science in UNICEF learning centres, funded with EU humanitarian support.

When asked to introduce herself in English, the first thing Haresa says is: “I am from Camp 15”.

She’s been living here for the past four and a half years. When she lived Myanmar, she couldn’t speak Burmese as it is taught in school and she had not yet started school.

Her best friend Shokatara echoes this sentiment. “I‘m happy that I can learn Burmese now. I want to go back to Myanmar and teach it to Rohingya children there.”